- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 29 833

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

Eight to nine years ago, the Windows world was full of companies who thought it would be a great idea to turn a Windows phone into a PC. Now, almost a decade later, a major peripheral company says that it’s time once again.

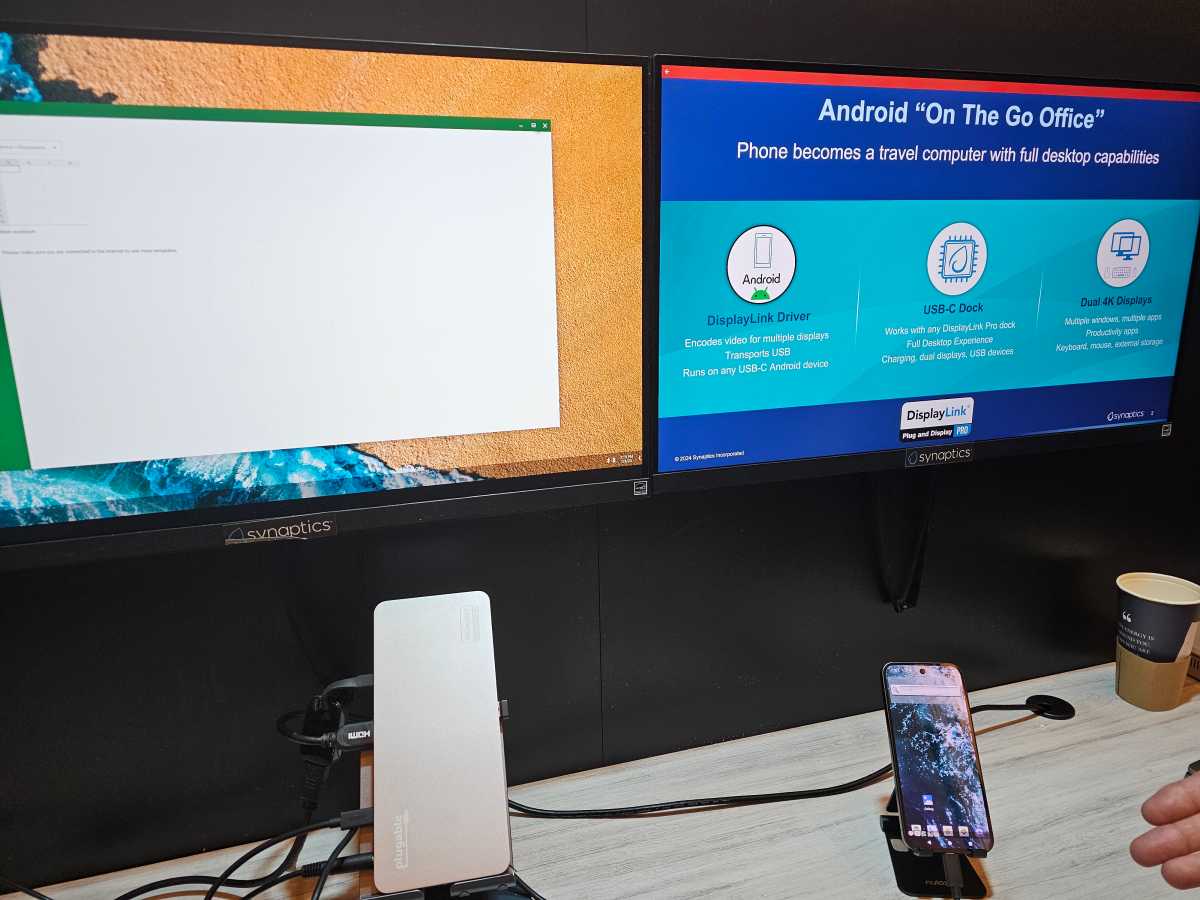

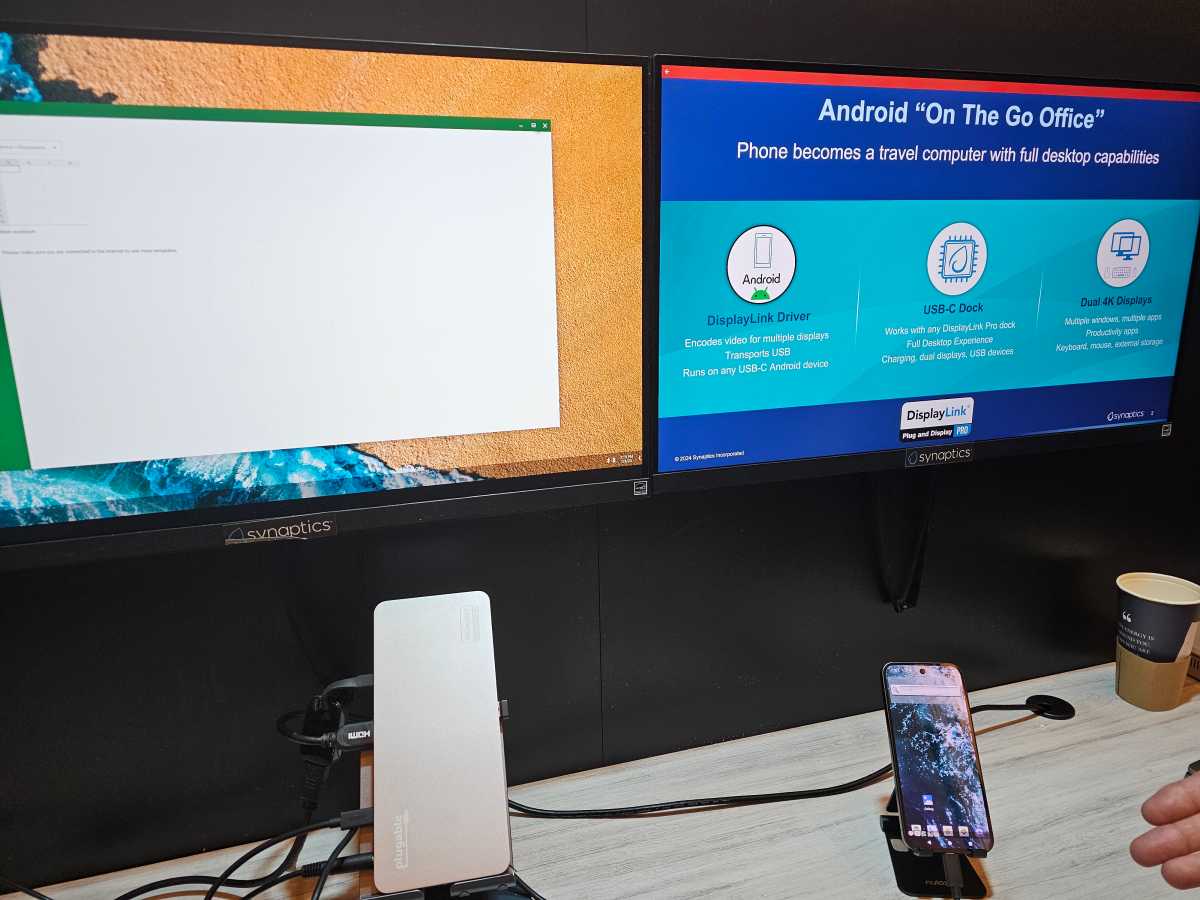

DisplayLink, which is owned by Synaptics, used CES to start pitching the idea of connecting an Android phone via a USB-C cable to a DisplayLink docking station. The company demonstrated a physical link to the dock, with a pair of connected displays using the phone’s CPU and GPU to render images. It also showed off a wireless version, with a connection running on top of Wi-Fi to an external dongle.

But there’s an important distinction: These phones don’t just mirror the home screen. Instead, they act like a typical multi-monitor Windows setup, with each display showing its own content, apart from what’s displayed on the phone.

That’s a small but significant change from Microsoft Continuum, the solution of yore for connecting your Windows 10 Mobile smartphone to a mouse, keyboard, and display. The problem? Continuum didn’t really work. While Continuum sounded great on paper, it was slow, laggy, and buggy. Innovations like the HP Lap Dock didn’t quite solve its problems, either.

In this DisplayLink demonstration, an Android phone is connected via USB-C and DisplayLink to a DisplayLink dock, and then to two external displays.

Mark Hachman / IDG

Now, executives at Synpatics think that modern smartphones offer the same hardware capabilities as a modern Core i5 processor, with integrated graphics.

“We put a DisplayLink driver on this phone, and now you can come into a meeting like you’re going to charge your phone,” a DisplayLink representative said. “Now you can hook [the phone] up to the same dock you hooked up to your PC, but you can drive two 4K, 60-hertz displays, keyboard, and mouse. You can access flash drives, everything you can do. There’s no real difference.”

On the PC, the DisplayLink technology works by compressing the information that passes over the cable to the screen, in a conceptually similar manner to how Netflix compresses data that it displays on a TV screen or monitor — the compression occurs, but any degradation in visual quality isn’t readily noticeable. The issue there is that DisplayLink requires a software driver to work. (The company is now referring to it as a “virtual graphics card.”)

What that means, however, is that DisplayLink would either have to be sideloaded in, or supported by the phone maker or by Google.

Other companies do this today; Samsung’s DeX can use an external display to run Android apps, for example.

What DisplayLink hopes to do is convince phone makers that their hardware can be used to provide multi-monitor setups, much like the PC; and start investing in external hardware and docks to support them. That’s where Synaptics (and DisplayLink) can make its money.

Continuum wasn’t all that hot, and it’s not clear how well-utilized Samsung’s DeX actually is. But there’s a chunk of the population that’s really wedded to their phones. For them, maybe it’s time to take an old technology and make it new again.

DisplayLink, which is owned by Synaptics, used CES to start pitching the idea of connecting an Android phone via a USB-C cable to a DisplayLink docking station. The company demonstrated a physical link to the dock, with a pair of connected displays using the phone’s CPU and GPU to render images. It also showed off a wireless version, with a connection running on top of Wi-Fi to an external dongle.

But there’s an important distinction: These phones don’t just mirror the home screen. Instead, they act like a typical multi-monitor Windows setup, with each display showing its own content, apart from what’s displayed on the phone.

That’s a small but significant change from Microsoft Continuum, the solution of yore for connecting your Windows 10 Mobile smartphone to a mouse, keyboard, and display. The problem? Continuum didn’t really work. While Continuum sounded great on paper, it was slow, laggy, and buggy. Innovations like the HP Lap Dock didn’t quite solve its problems, either.

In this DisplayLink demonstration, an Android phone is connected via USB-C and DisplayLink to a DisplayLink dock, and then to two external displays.

Mark Hachman / IDG

Now, executives at Synpatics think that modern smartphones offer the same hardware capabilities as a modern Core i5 processor, with integrated graphics.

“We put a DisplayLink driver on this phone, and now you can come into a meeting like you’re going to charge your phone,” a DisplayLink representative said. “Now you can hook [the phone] up to the same dock you hooked up to your PC, but you can drive two 4K, 60-hertz displays, keyboard, and mouse. You can access flash drives, everything you can do. There’s no real difference.”

On the PC, the DisplayLink technology works by compressing the information that passes over the cable to the screen, in a conceptually similar manner to how Netflix compresses data that it displays on a TV screen or monitor — the compression occurs, but any degradation in visual quality isn’t readily noticeable. The issue there is that DisplayLink requires a software driver to work. (The company is now referring to it as a “virtual graphics card.”)

What that means, however, is that DisplayLink would either have to be sideloaded in, or supported by the phone maker or by Google.

Other companies do this today; Samsung’s DeX can use an external display to run Android apps, for example.

What DisplayLink hopes to do is convince phone makers that their hardware can be used to provide multi-monitor setups, much like the PC; and start investing in external hardware and docks to support them. That’s where Synaptics (and DisplayLink) can make its money.

Continuum wasn’t all that hot, and it’s not clear how well-utilized Samsung’s DeX actually is. But there’s a chunk of the population that’s really wedded to their phones. For them, maybe it’s time to take an old technology and make it new again.