Some financial analysts worry that artificial intelligence may not justify the massive investments being made in the field. While I understand their concerns, I see things differently. I’m neither an AI Boomer nor an AI Doomer — I believe AI has the potential to drive innovation, enhance productivity, and deliver measurable business outcomes.

In my last article, I explored how Large Language Models (LLMs) can be used to structure unstructured data. This time, I want to go a step further: demonstrating how the outcome of structuring data with LLMs can serve as the foundation for building intelligent applications. Thus showing how to integrate AI in a bigger picture.

In this article, I’ll share how I used a modern stack to fast-track the development and deployment of Baker — a smart app which is the result of transforming a raw recipes dataset into an easy to use solution. This journey highlights more than just technical implementation; it showcases how AI can address practical challenges and deliver tangible value in real-world scenarios.

Baker: Your Cooking Muse

In The (lesser-known) rising application of LLMs, I mentioned that I needed a recipes dataset to work on a personal project. Now, it’s time to reveal that project.

Photo by WebFactory Ltd on Unsplash

Managing food has always been a challenge for me. I struggle to find inspiration for meals, and as a result, I often let ingredients go to waste — something I’ve wanted to change for a long time. That’s why I set out to create a recipe recommender system that helps me (and others) use up ingredients before they go stale. The solution? Baker, my prototype for tackling this issue. This project reflects my passion for leveraging AI to tackle everyday challenges like food waste.

Baker is an open-source web application in its early stages, built almost entirely in Python. The app takes a list of ingredients and their quantities — mimicking what you might find in your fridge and pantry — and suggests recipes you can prepare using those ingredients. It’s designed to simplify meal preparation while encouraging smarter, more sustainable food choices. You can try the app yourself here:

⇒ mixit-baker.streamlit.app

However, you might want to read the remaining of the article first. In one of the next sections , I’ll walk you through a demo of the application.

From Idea to POC: Accelerated Development with AI and Modern Tools

After the initial parsing of the dataset, I became busy with other duties and set this side project aside for months 😉. But technology evolves quickly. When I finally returned to it, a series of newer models, techniques, and tools had emerged or matured, providing an opportunity to revisit and enhance the project.

Revisiting Data Extraction with GPT-4o

The first step was to revisit my earlier work on data extraction and update the results. In my previous iteration, I had used MistralAI’s open-mixtral-8x7b, which had since been deprecated. This time, I switched to the newer and more advanced GPT-4o, and the results were remarkable.

To put the improvement into perspective:

This milestone reflects how quickly AI capabilities improve. Just months ago, LLMs often struggled to output valid JSON reliably. This iteration demonstrated not only better results but also how adopting newer tools can yield substantial gains.

Post-Processing Challenges

Even with improved extraction, the raw data required significant post-processing. Recipes featured inconsistent units — grams, teaspoons, cups, and more — making comparisons and recommendations challenging. To address this, I adopted a systematic approach:

This normalization step was essential for enabling accurate ingredient filtering and powering the recipe recommendation engine. It also underscored a critical point: AI outputs must be contextually meaningful for their intended application, not just technically correct.

Building the Engine and Web Application

With the data cleaned, standardized, and ready for use, the next step was to start leveraging the data which I did by building the engine logic and wrapping it in a web app.

Quick Prototyping

Throughout Baker’s development, I embraced a quick prototyping philosophy. The goal was less building an app from day one but rather to explore tools and techniques, test ideas and gather feedback.

From Notebooks to a POC app:

The way I built my data pipeline and the web app using AI illustrate the quick prototyping philosophy.

By adopting this approach, I was able to build a working MVP in days rather than weeks or months.

Open-Source:

A marker of Baker is its open-source nature. By sharing the project on GitHub, I hope to:

Open-sourcing makes it easier for others to reproduce results, contribute improvements, and exchange ideas. Collaboration not only strengthens Baker but also fosters collective innovation.

Free Deployment: Accessible and Lightweight

To make Baker accessible, I deployed it using free-tier services:

These platforms allowed me to deploy quickly and experiment without the financial or technical barriers of traditional hosting solutions. This deployment strategy highlights how modern tools make it possible to turn creative ideas into accessible applications at little to no cost.

Behind the Scenes: The Technology Powering Baker

In this section, I’ll share some implementation details of Baker. Again it is open-source so I invite my technical readers to go check the code on GitHub. Some readers might want to jump to the next section.

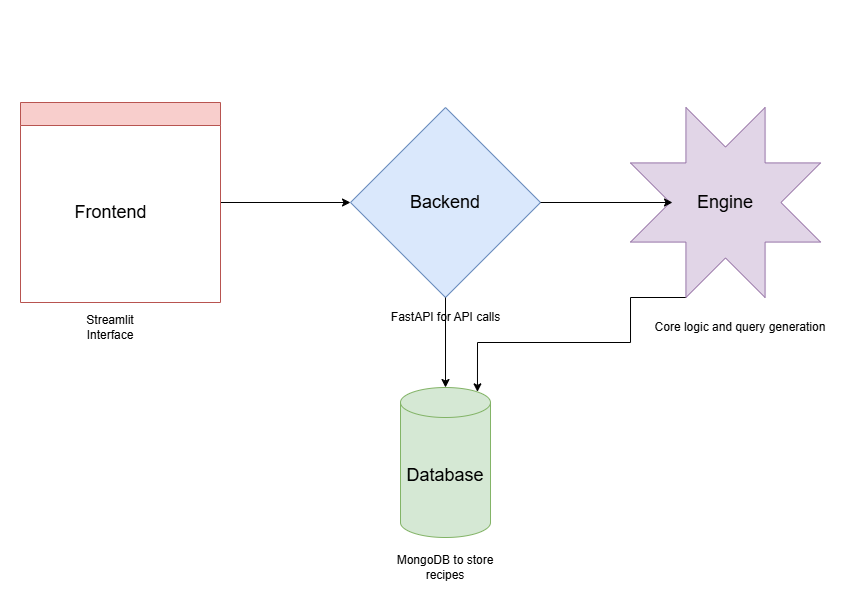

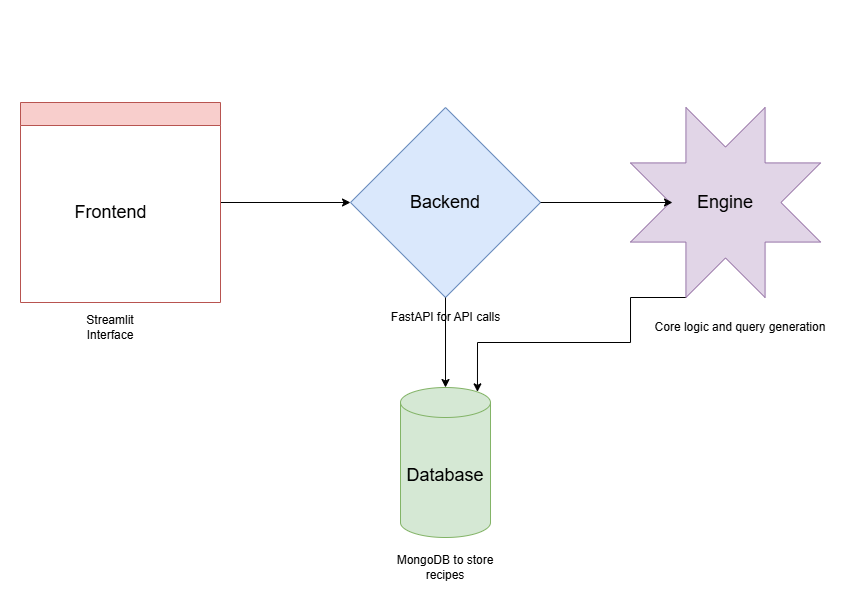

The application is minimalist with a simple 3 tier architecture and is built almost entirely in Python.

Photo by author

It is made of the following components:

The backend is initialized in app.py, where FastAPI endpoints are defined. For instance:

from fastapi import FastAPI

from baker.engine.core import find_recipes

from baker.models.ingredient import Ingredient

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/")

def welcome():

return {"message": "Welcome to the Baker API!"}

@app.post("/recipes")

def _find_recipes(ingredients: list[Ingredient], serving_size: int = 1) -> list[dict]:

return find_recipes(ingredients, serving_size)

The /recipes endpoint accepts a list of ingredients and a serving size then delegates the processing to the engine.

Recipe Engine Logic

The heart of the application resides in core.py within the engine directory. It manages database connections and query pipelines. Below is an example of the find_recipes function:

# Imports and the get_recipes_collection function are not included

def find_recipes(ingredients, serving_size=1):

# Get the recipes collection

recipes = get_recipes_collection()

# Create the pipeline

pipeline = Pipeline()

pipeline = include_normalization_steps(pipeline, serving_size)

query = generate_match_query(ingredients, serving_size)

print(query)

pipeline.match(query=query).project(

include=[

"id",

"title",

"preparation_time",

"cooking_time",

"original_serving_size",

"serving_size",

"ingredients",

"steps",

],

exclude="_id",

)

# Find the recipes

result = recipes.aggregate(pipeline.export()).to_list(length=None)

return result

def generate_match_query(ingredients: list[Ingredient], serving_size: int = 1) -> dict:

"""Generate the match query."""

operands = []

for ingredient in ingredients:

operand = {

"ingredients.name": ingredient.name,

"ingredients.unit": ingredient.unit,

"ingredients.quantity": {"$gte": ingredient.quantity / serving_size},

}

operands.append(operand)

query = {"$and": operands}

return query

def include_normalization_steps(pipeline: Pipeline, serving_size: int = 1):

"""Adds steps in a pipeline to normalize the ingredients quantity in the db

The steps below normalize the quantities of the ingredients in the recipes in the DB by the recipe serving size.

"""

# Unwind the ingredients

pipeline.unwind(path="$ingredients")

pipeline.add_fields({"original_serving_size": "$serving_size"})

# Add the normalized quantity

pipeline.add_fields(

{

# "orignal_serving_size": "$serving_size",

"serving_size": serving_size,

"ingredients.quantity": S.multiply(

S.field("ingredients.quantity"),

S.divide(serving_size, S.max([S.field("serving_size"), 1])),

),

}

)

# Group the results

pipeline.group(

by="_id",

query={

"id": {"$first": "$id"},

"title": {"$first": "$title"},

"original_serving_size": {"$first": "$original_serving_size"},

"serving_size": {"$first": "$serving_size"},

"preparation_time": {"$first": "$preparation_time"},

"cooking_time": {"$first": "$cooking_time"},

# "directions_source_text": {"$first": "$directions_source_text"},

"ingredients": {"$addToSet": "$ingredients"},

"steps": {"$first": "$steps"},

},

)

return pipeline

The core logic of Baker resides in the find_recipes function.

This function creates a MongoDB aggregation pipeline thanks to monggregate. This aggregation pipeline includes several steps.

The first steps are generated by the include_normalization_steps function that is going to dynamically update the quantities of the ingredients in the database to ensure we are comparing apples to apples. This is done by updating the ingredients quantities in the database to the user desired serving.

Then the actual matching logic is created by the generate_match_query function. Here we ensure, that the recipes don’t require more than what the user have for the ingredients concerned.

Finally a projection filters out the fields that we don’t need to return.

User Guide: Discovering Recipes with Baker in a Few Clicks

Baker helps you discover a better fate for your ingredients by finding recipes that match what you already have at home.

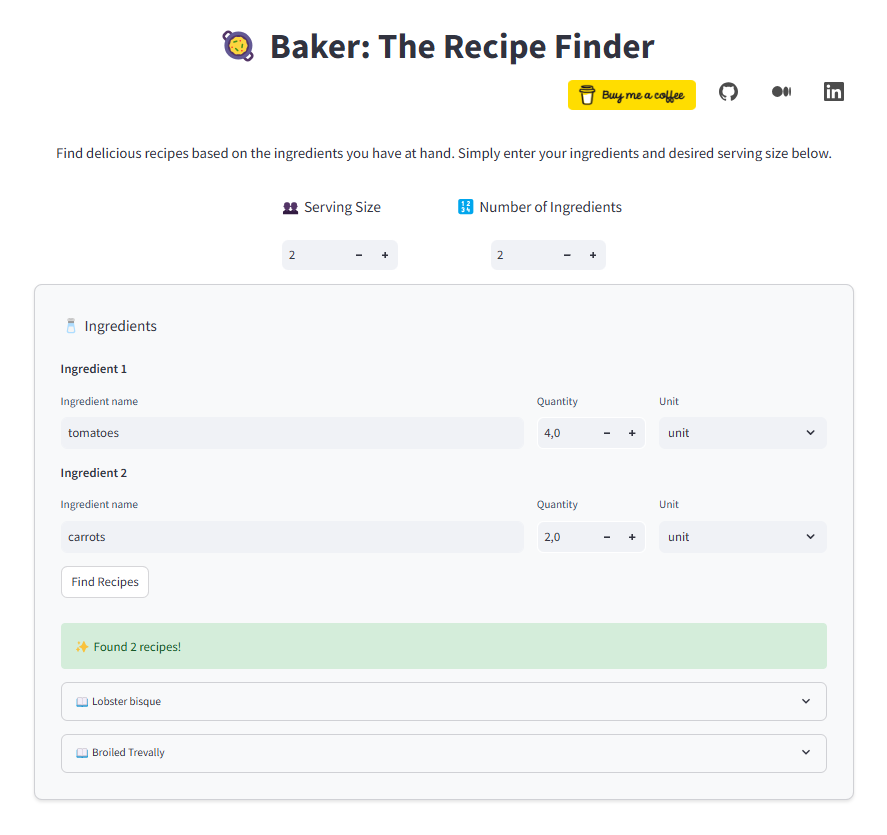

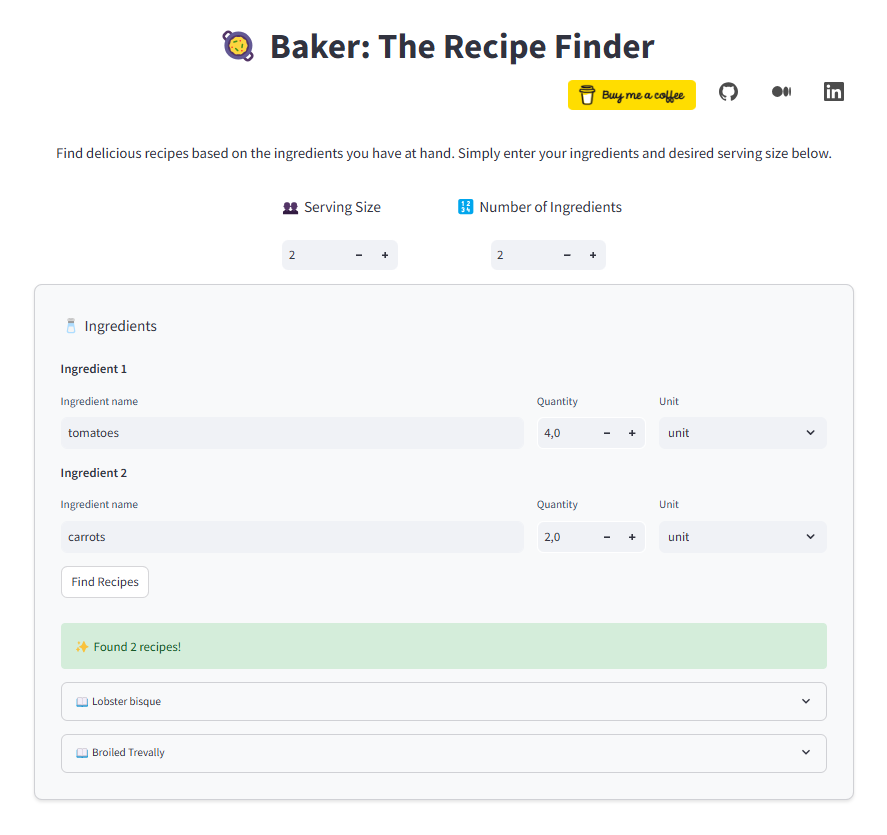

The app features a simple form-based interface. Enter the ingredients you have, specify their quantities, and select the unit of measurement from the available options.

Photo by author

In the example above, I’m searching for a recipe for two servings to use up 4 tomatoes and 2 carrots that have been sitting in my kitchen for a bit too long.

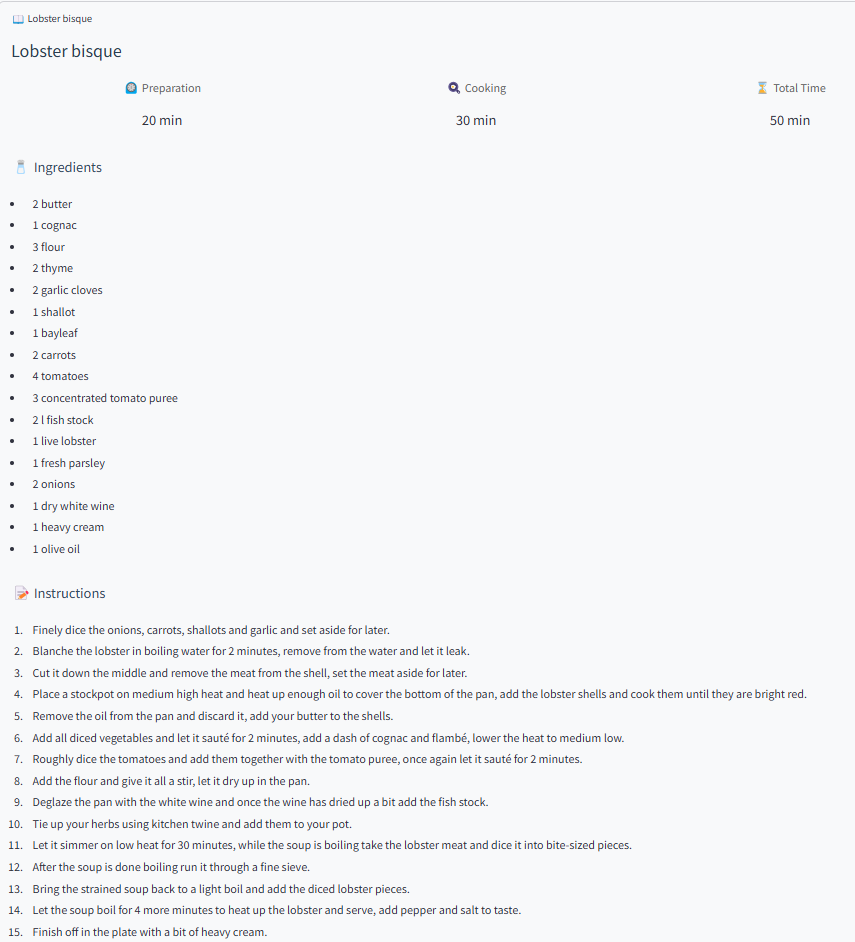

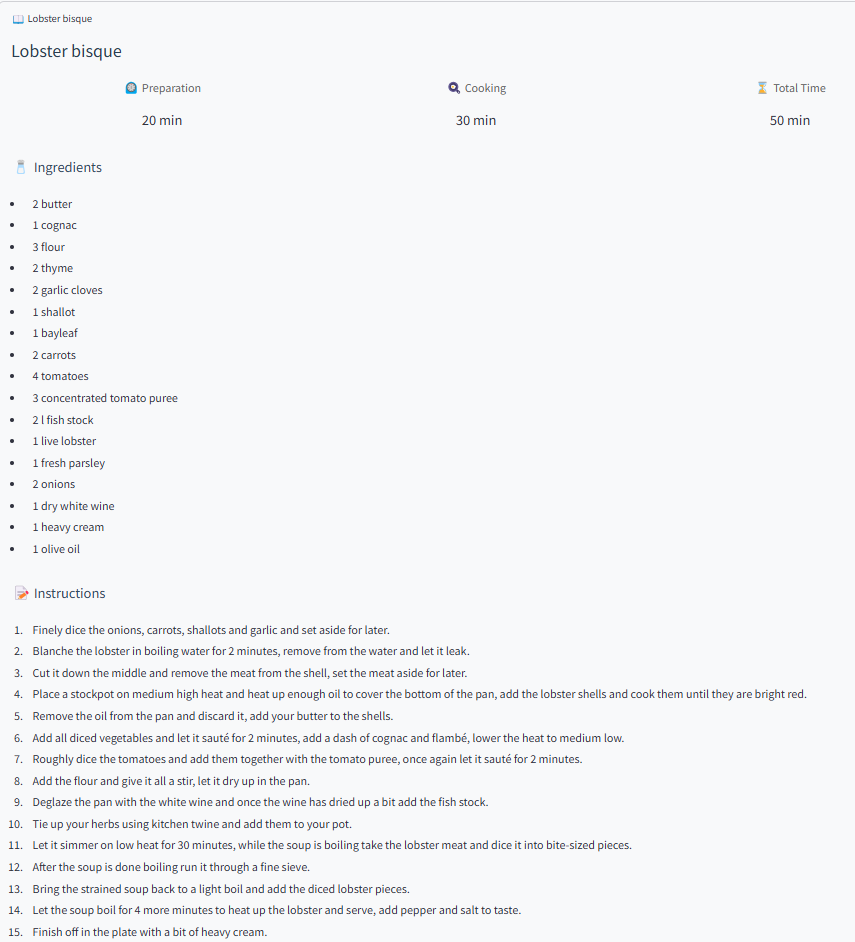

Baker found two recipes! Clicking on a recipe lets you view the full details.

Photo by author

Baker adapts the quantities in the recipe to match the serving size you’ve set. For example, if you adjust the serving size from two to four people, the app recalculates the ingredient quantities accordingly.

Updating the serving size may also change the recipes that appear. Baker ensures that the suggested recipes match not only the serving size but also the ingredients and quantities you have on hand. For instance, if you only have 4 tomatoes and 2 carrots for two people, Baker will avoid recommending recipes that require 4 tomatoes and 4 carrots.

The Road Ahead: Scaling Baker for Broader Impact

Baker is a side project developed quickly and pragmatically, a functional prototype rather than a production-ready application.

However, I’d love to see it grow into something more impactful.

There are several areas where the app can expand, both in functionality and sophistication. To move forward, let’s address its current limitations and explore possible enhancements.

1 — Growing the Recipe Database

Baker’s recipes originate from Public Domain Recipes, an open-source database of recipes. While this is an amazing project, the number of available recipes is limited. As a result, Baker only knows 360 recipes for now. To put this into perspective, some dedicated recipe websites claim to have tens of thousands recipes.

To scale, I’ll need to identify additional data sources for recipes.

2 — Improving the Data Ingestion Pipeline

At the moment, data ingestion is handled through Jupyter Notebooks. One of the main technical priorities is to transform these notebooks into robust Python scripts, integrate them into an admin section of Baker, or even spin them off into a dedicated app.

Additionally, I am convinced that there’s room for improving the parsing process performed by the LLMs to ensure greater consistency and accuracy.

3 — Adding Semantic Search & Flexibility

Currently, recipes are searched by ingredient names through exact string matching. For example, searching for “tomato” will not retrieve recipes that mention “tomatoes.” This can be addressed by implementing a semantic search approach using vector databases. With semantic search, variations of ingredient names — whether due to pluralization, regional differences, or translation — can be dynamically mapped to the same concept.

Moreover, semantic search would allow users to search in their native language, further broadening accessibility.

I also want to introduce greater flexibility in the search functionality. For example, if a user searches for recipes with tomatoes, carrots, and bananas but no such combination exists in the database, the search should still return recipes with subsets of the entered ingredients (e.g., tomatoes and carrots, tomatoes and bananas, or carrots and bananas).

From a feature standpoint, this is my top priority.

Other Enhancements to Consider

While the above are the main focus areas, there are plenty of other topics I’d like to address:

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this journey of turning ideas into reality. If you did, consider supporting me on Buy Me a Coffee to help fund future developments. Now, let’s summarize the key takeaways.

Earlier this year, I wrote an article about how using LLMs for data structuration and extraction was a promising use case powered by the new Generative AI wave. In this follow-up, I’ve taken the concept further by demonstrating a tangible outcome: using a LLM-generated dataset to power a data-centric smart app, Baker.

Along the way, I aimed to show how this process has become more accessible with modern tools like Streamlit, FastAPI, Streamlit Cloud, Koyeb, and Cursor. If you want a deep dive on the tools I used, let me know in the comments.

These tools provide the flexibility and accessibility needed to focus on solving real problems rather than being overwhelmed by the complexity of managing multiple aspects — data pipelines, backend logic, frontend interfaces, CI/CD workflows, cloud deployments, testing, and the intricacies of various programming languages.

But this project isn’t just about recipes — it’s about unlocking the potential of unstructured data to solve real-world problems. For instance, the same approach used in Baker could be applied to create a personalized learning platform. By structuring educational content, such as lecture transcripts or articles, into accessible formats and building a recommendation engine, one could help users discover relevant learning materials based on their goals or interests.

Whether for education, product recommendations, or knowledge management, the principles and tools I’ve shared here can inspire countless applications.

As we step into the new year, I encourage you to reflect on your own untapped datasets and ideas. What could you build with the tools and knowledge shared here? With small steps, quick iterations, and a collaborative mindset, you, too, can create innovative solutions that make a difference.

Here’s to building a smarter, more data-driven future — together.

Transforming Data into Solutions: Building a Smart App with Python and AI was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

In my last article, I explored how Large Language Models (LLMs) can be used to structure unstructured data. This time, I want to go a step further: demonstrating how the outcome of structuring data with LLMs can serve as the foundation for building intelligent applications. Thus showing how to integrate AI in a bigger picture.

In this article, I’ll share how I used a modern stack to fast-track the development and deployment of Baker — a smart app which is the result of transforming a raw recipes dataset into an easy to use solution. This journey highlights more than just technical implementation; it showcases how AI can address practical challenges and deliver tangible value in real-world scenarios.

Baker: Your Cooking Muse

In The (lesser-known) rising application of LLMs, I mentioned that I needed a recipes dataset to work on a personal project. Now, it’s time to reveal that project.

Photo by WebFactory Ltd on Unsplash

Managing food has always been a challenge for me. I struggle to find inspiration for meals, and as a result, I often let ingredients go to waste — something I’ve wanted to change for a long time. That’s why I set out to create a recipe recommender system that helps me (and others) use up ingredients before they go stale. The solution? Baker, my prototype for tackling this issue. This project reflects my passion for leveraging AI to tackle everyday challenges like food waste.

Baker is an open-source web application in its early stages, built almost entirely in Python. The app takes a list of ingredients and their quantities — mimicking what you might find in your fridge and pantry — and suggests recipes you can prepare using those ingredients. It’s designed to simplify meal preparation while encouraging smarter, more sustainable food choices. You can try the app yourself here:

⇒ mixit-baker.streamlit.app

However, you might want to read the remaining of the article first. In one of the next sections , I’ll walk you through a demo of the application.

From Idea to POC: Accelerated Development with AI and Modern Tools

After the initial parsing of the dataset, I became busy with other duties and set this side project aside for months 😉. But technology evolves quickly. When I finally returned to it, a series of newer models, techniques, and tools had emerged or matured, providing an opportunity to revisit and enhance the project.

Revisiting Data Extraction with GPT-4o

The first step was to revisit my earlier work on data extraction and update the results. In my previous iteration, I had used MistralAI’s open-mixtral-8x7b, which had since been deprecated. This time, I switched to the newer and more advanced GPT-4o, and the results were remarkable.

To put the improvement into perspective:

- In the earlier run, the LLM failed to parse 89 recipes due to inconsistencies in JSON generation.

- With GPT-4o, all 360 recipes in the dataset were parsed successfully, achieving a 100% success rate.

This milestone reflects how quickly AI capabilities improve. Just months ago, LLMs often struggled to output valid JSON reliably. This iteration demonstrated not only better results but also how adopting newer tools can yield substantial gains.

Post-Processing Challenges

Even with improved extraction, the raw data required significant post-processing. Recipes featured inconsistent units — grams, teaspoons, cups, and more — making comparisons and recommendations challenging. To address this, I adopted a systematic approach:

- Standardization: I defined a restricted set of units (e.g., grams for weight, milliliters for volume).

- Mapping and Conversion: All original units were mapped to this subset, with quantities adjusted accordingly.

This normalization step was essential for enabling accurate ingredient filtering and powering the recipe recommendation engine. It also underscored a critical point: AI outputs must be contextually meaningful for their intended application, not just technically correct.

Building the Engine and Web Application

With the data cleaned, standardized, and ready for use, the next step was to start leveraging the data which I did by building the engine logic and wrapping it in a web app.

Quick Prototyping

Throughout Baker’s development, I embraced a quick prototyping philosophy. The goal was less building an app from day one but rather to explore tools and techniques, test ideas and gather feedback.

From Notebooks to a POC app:

The way I built my data pipeline and the web app using AI illustrate the quick prototyping philosophy.

- The Data Pipeline: The entire pipeline for extraction and post-processing resides in Jupyter notebooks. While this setup is “minimal yet functional” compared to a full-fledged ETL pipeline, it provided the speed and flexibility to iterate quickly. Initially, I thought of it as a one-time process, but I’m now planning to transform it into something more robust and repeatible.

- The Web App: The web app leverages FastAPI for the backend and Streamlit for the frontend. These frameworks are accessible, developer-friendly, and perfect for rapidly prototyping interactive applications.

- Accelerated Development with AI: The frontend was generated entirely using Cursor, an AI-powered development tool. While I had heard of Cursor before, this project allowed me to fully explore its potential. The experience was so enjoyable that I plan to write a dedicated article about it.

By adopting this approach, I was able to build a working MVP in days rather than weeks or months.

Open-Source:

A marker of Baker is its open-source nature. By sharing the project on GitHub, I hope to:

- Encourage Collaboration: Enable others to contribute new features, enhance the codebase, or extend the application with additional datasets.

- Inspire Learning: Provide a practical resource for those curious about leveraging LLMs, structuring unstructured data, or building recommendation systems.

Open-sourcing makes it easier for others to reproduce results, contribute improvements, and exchange ideas. Collaboration not only strengthens Baker but also fosters collective innovation.

Free Deployment: Accessible and Lightweight

To make Baker accessible, I deployed it using free-tier services:

- Streamlit Cloud: Powers the frontend, delivering an intuitive and interactive user experience.

- Koyeb: Supports backend processing and API calls without incurring hosting costs.

These platforms allowed me to deploy quickly and experiment without the financial or technical barriers of traditional hosting solutions. This deployment strategy highlights how modern tools make it possible to turn creative ideas into accessible applications at little to no cost.

Behind the Scenes: The Technology Powering Baker

In this section, I’ll share some implementation details of Baker. Again it is open-source so I invite my technical readers to go check the code on GitHub. Some readers might want to jump to the next section.

The application is minimalist with a simple 3 tier architecture and is built almost entirely in Python.

Photo by author

It is made of the following components:

- Frontend: A Streamlit interface provides an intuitive platform for users to interact with the system, query recipes, and receive recommendations.

- Backend: Built with FastAPI, the backend serves as the interface for handling user queries and delivering recommendations.

- Engine: The engine contains the core logic for finding and filtering recipes, leveraging monggregate as a query builder.

- Database: The recipes are stored in a MongoDB database that processes the aggregation pipelines generated by the engine.

The backend is initialized in app.py, where FastAPI endpoints are defined. For instance:

from fastapi import FastAPI

from baker.engine.core import find_recipes

from baker.models.ingredient import Ingredient

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/")

def welcome():

return {"message": "Welcome to the Baker API!"}

@app.post("/recipes")

def _find_recipes(ingredients: list[Ingredient], serving_size: int = 1) -> list[dict]:

return find_recipes(ingredients, serving_size)

The /recipes endpoint accepts a list of ingredients and a serving size then delegates the processing to the engine.

Recipe Engine Logic

The heart of the application resides in core.py within the engine directory. It manages database connections and query pipelines. Below is an example of the find_recipes function:

# Imports and the get_recipes_collection function are not included

def find_recipes(ingredients, serving_size=1):

# Get the recipes collection

recipes = get_recipes_collection()

# Create the pipeline

pipeline = Pipeline()

pipeline = include_normalization_steps(pipeline, serving_size)

query = generate_match_query(ingredients, serving_size)

print(query)

pipeline.match(query=query).project(

include=[

"id",

"title",

"preparation_time",

"cooking_time",

"original_serving_size",

"serving_size",

"ingredients",

"steps",

],

exclude="_id",

)

# Find the recipes

result = recipes.aggregate(pipeline.export()).to_list(length=None)

return result

def generate_match_query(ingredients: list[Ingredient], serving_size: int = 1) -> dict:

"""Generate the match query."""

operands = []

for ingredient in ingredients:

operand = {

"ingredients.name": ingredient.name,

"ingredients.unit": ingredient.unit,

"ingredients.quantity": {"$gte": ingredient.quantity / serving_size},

}

operands.append(operand)

query = {"$and": operands}

return query

def include_normalization_steps(pipeline: Pipeline, serving_size: int = 1):

"""Adds steps in a pipeline to normalize the ingredients quantity in the db

The steps below normalize the quantities of the ingredients in the recipes in the DB by the recipe serving size.

"""

# Unwind the ingredients

pipeline.unwind(path="$ingredients")

pipeline.add_fields({"original_serving_size": "$serving_size"})

# Add the normalized quantity

pipeline.add_fields(

{

# "orignal_serving_size": "$serving_size",

"serving_size": serving_size,

"ingredients.quantity": S.multiply(

S.field("ingredients.quantity"),

S.divide(serving_size, S.max([S.field("serving_size"), 1])),

),

}

)

# Group the results

pipeline.group(

by="_id",

query={

"id": {"$first": "$id"},

"title": {"$first": "$title"},

"original_serving_size": {"$first": "$original_serving_size"},

"serving_size": {"$first": "$serving_size"},

"preparation_time": {"$first": "$preparation_time"},

"cooking_time": {"$first": "$cooking_time"},

# "directions_source_text": {"$first": "$directions_source_text"},

"ingredients": {"$addToSet": "$ingredients"},

"steps": {"$first": "$steps"},

},

)

return pipeline

The core logic of Baker resides in the find_recipes function.

This function creates a MongoDB aggregation pipeline thanks to monggregate. This aggregation pipeline includes several steps.

The first steps are generated by the include_normalization_steps function that is going to dynamically update the quantities of the ingredients in the database to ensure we are comparing apples to apples. This is done by updating the ingredients quantities in the database to the user desired serving.

Then the actual matching logic is created by the generate_match_query function. Here we ensure, that the recipes don’t require more than what the user have for the ingredients concerned.

Finally a projection filters out the fields that we don’t need to return.

User Guide: Discovering Recipes with Baker in a Few Clicks

Baker helps you discover a better fate for your ingredients by finding recipes that match what you already have at home.

The app features a simple form-based interface. Enter the ingredients you have, specify their quantities, and select the unit of measurement from the available options.

Photo by author

In the example above, I’m searching for a recipe for two servings to use up 4 tomatoes and 2 carrots that have been sitting in my kitchen for a bit too long.

Baker found two recipes! Clicking on a recipe lets you view the full details.

Photo by author

Baker adapts the quantities in the recipe to match the serving size you’ve set. For example, if you adjust the serving size from two to four people, the app recalculates the ingredient quantities accordingly.

Updating the serving size may also change the recipes that appear. Baker ensures that the suggested recipes match not only the serving size but also the ingredients and quantities you have on hand. For instance, if you only have 4 tomatoes and 2 carrots for two people, Baker will avoid recommending recipes that require 4 tomatoes and 4 carrots.

The Road Ahead: Scaling Baker for Broader Impact

Baker is a side project developed quickly and pragmatically, a functional prototype rather than a production-ready application.

However, I’d love to see it grow into something more impactful.

There are several areas where the app can expand, both in functionality and sophistication. To move forward, let’s address its current limitations and explore possible enhancements.

1 — Growing the Recipe Database

Baker’s recipes originate from Public Domain Recipes, an open-source database of recipes. While this is an amazing project, the number of available recipes is limited. As a result, Baker only knows 360 recipes for now. To put this into perspective, some dedicated recipe websites claim to have tens of thousands recipes.

To scale, I’ll need to identify additional data sources for recipes.

2 — Improving the Data Ingestion Pipeline

At the moment, data ingestion is handled through Jupyter Notebooks. One of the main technical priorities is to transform these notebooks into robust Python scripts, integrate them into an admin section of Baker, or even spin them off into a dedicated app.

Additionally, I am convinced that there’s room for improving the parsing process performed by the LLMs to ensure greater consistency and accuracy.

3 — Adding Semantic Search & Flexibility

Currently, recipes are searched by ingredient names through exact string matching. For example, searching for “tomato” will not retrieve recipes that mention “tomatoes.” This can be addressed by implementing a semantic search approach using vector databases. With semantic search, variations of ingredient names — whether due to pluralization, regional differences, or translation — can be dynamically mapped to the same concept.

Moreover, semantic search would allow users to search in their native language, further broadening accessibility.

I also want to introduce greater flexibility in the search functionality. For example, if a user searches for recipes with tomatoes, carrots, and bananas but no such combination exists in the database, the search should still return recipes with subsets of the entered ingredients (e.g., tomatoes and carrots, tomatoes and bananas, or carrots and bananas).

From a feature standpoint, this is my top priority.

Other Enhancements to Consider

While the above are the main focus areas, there are plenty of other topics I’d like to address:

- UI enhancements

- Sorting and ranking of recipes

- Improved error handling and robustness

- Adopting software engineering best practices

- Performance optimization

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this journey of turning ideas into reality. If you did, consider supporting me on Buy Me a Coffee to help fund future developments. Now, let’s summarize the key takeaways.

Earlier this year, I wrote an article about how using LLMs for data structuration and extraction was a promising use case powered by the new Generative AI wave. In this follow-up, I’ve taken the concept further by demonstrating a tangible outcome: using a LLM-generated dataset to power a data-centric smart app, Baker.

Along the way, I aimed to show how this process has become more accessible with modern tools like Streamlit, FastAPI, Streamlit Cloud, Koyeb, and Cursor. If you want a deep dive on the tools I used, let me know in the comments.

These tools provide the flexibility and accessibility needed to focus on solving real problems rather than being overwhelmed by the complexity of managing multiple aspects — data pipelines, backend logic, frontend interfaces, CI/CD workflows, cloud deployments, testing, and the intricacies of various programming languages.

But this project isn’t just about recipes — it’s about unlocking the potential of unstructured data to solve real-world problems. For instance, the same approach used in Baker could be applied to create a personalized learning platform. By structuring educational content, such as lecture transcripts or articles, into accessible formats and building a recommendation engine, one could help users discover relevant learning materials based on their goals or interests.

Whether for education, product recommendations, or knowledge management, the principles and tools I’ve shared here can inspire countless applications.

As we step into the new year, I encourage you to reflect on your own untapped datasets and ideas. What could you build with the tools and knowledge shared here? With small steps, quick iterations, and a collaborative mindset, you, too, can create innovative solutions that make a difference.

Here’s to building a smarter, more data-driven future — together.

Transforming Data into Solutions: Building a Smart App with Python and AI was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.