- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 40 948

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

“Smell added an emotional and sensory depth that text labels alone could never provide.”

Visitors sniffing the "Scent of the Afterlife" card during a guided tour at the Museum August Kestner, Hannover, Germany Credit: Ulriki Dubiel/S.C. Ehrich et a;, 2026/CC BY

In 2023, scientists identified the compounds in the balms used to mummify the organs of an ancient Egyptian noblewoman, suggesting that the recipes were unusually complex and used ingredients not native to the region. The authors also partnered with a perfumer to re-create what co-author Barbara Huber (of the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and the University of Tübingen) dubbed “the scent of eternity.” Now Huber has collaborated with the curators of two museums to incorporate that eternal scent into exhibits on ancient Egypt to transform how visitors understand embalming.

As previously reported, Egyptian embalming is thought to have begun in the Predynastic Period or earlier, when people noticed that the arid desert heat tended to dry and preserve bodies buried in the desert. Eventually, the idea of preserving the body after death worked its way into Egyptian religious beliefs. When people began burying the dead in rock tombs, away from the desiccating sand, they used chemicals like natron salt and plant-based resins for embalming.

The procedure typically began by laying the corpse on a table and removing the internal organs—except for the heart. Per Greek historian Herodotus, “They first draw out part of the brain through the nostrils with an iron hook, and inject certain drugs into the rest” to liquefy the remaining brain matter. Next, they washed out the body cavity with spices and palm wine, sewed the body back up, and left aromatic plants and spices inside, including bags of natron. The body was then allowed to dehydrate over 40 days. The dried organs were sealed in canopic jars (or sometimes put back into the body cavity). Then the body was wrapped in several layers of linen cloth, with amulets placed within those layers to protect the deceased from evil. The fully wrapped mummy was coated in resin to keep moisture out and placed in a coffin (also sealed with resin).

Most of what we know about ancient Egyptian mummification techniques comes from a few ancient texts. In addition to a text called The Ritual of Embalming, Herodotus, in his Histories, mentions the use of natron to dehydrate the body. But there are very few details about the specific spices, oils, resins, and other ingredients used. Science can help fill in the gaps, particularly given the expanding array of methods for conducting biomolecular analysis, including various forms of gas chromatography.

For example, a 2018 study analyzed organic residues from the mummy’s wrappings with a technique called gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. They found that the wrappings were saturated with a mixture of plant oil, an aromatic plant extract, a gum or sugar, and heated conifer resin. A new paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science analyzed the chemical compositions of the odor-carrying volatile organic compounds (VOCs) associated with a broad sampling of balms and mummy tissues. The idea was to determine which odors were associated with organic embalming agents and which might have arisen from the process of decay.

Capturing the scent of the afterlife

Huber has previously worked on reconstructing residues on ancient incense burners excavated from Tayma, a walled oasis settlement in what is now Saudi Arabia that was part of a trade network—known as the Incense Route because it primarily transported frankincense and myrrh. Huber then turned her attention to Egyptian mummification. While most prior similar studies focused on samples gleaned from the bandages and tissues of actual mummies, she focused on the balms used to embalm accompanying organs stored in canopic jars.

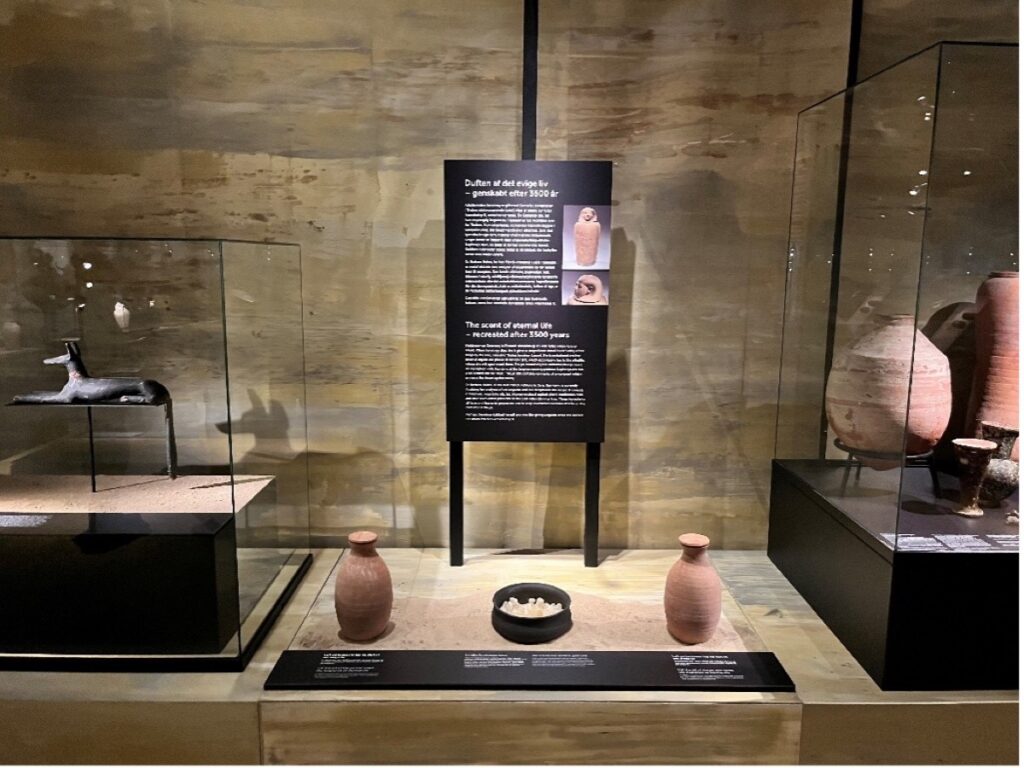

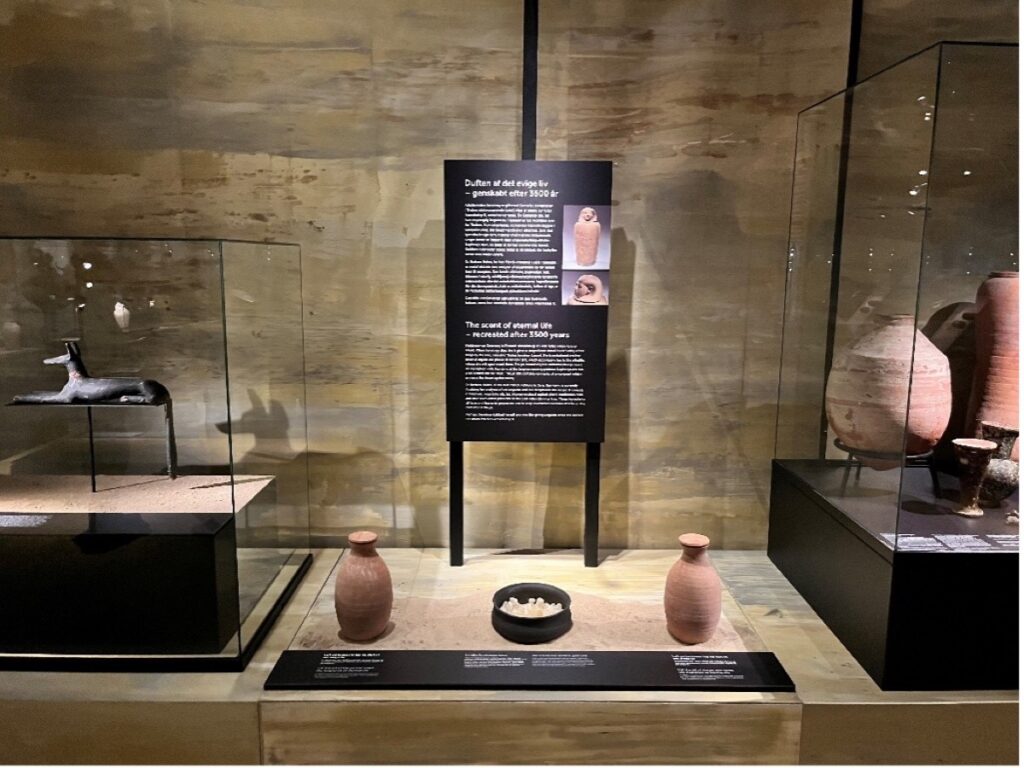

Museum display at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark. Barbara Huber/S.C. Ehrich et a;, 2026/CC BY

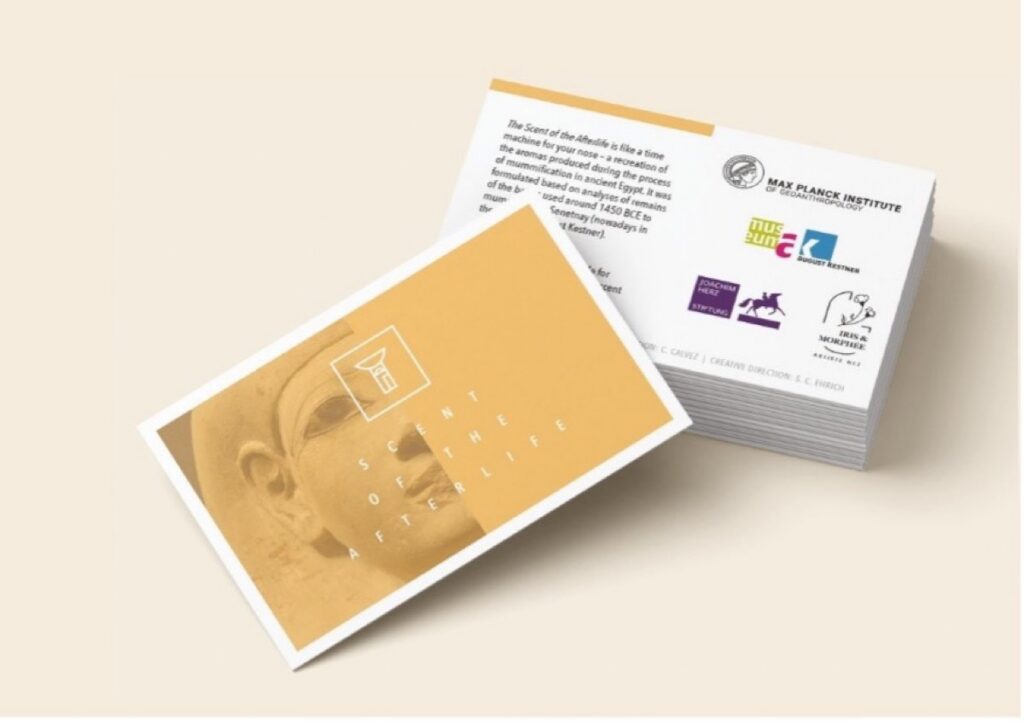

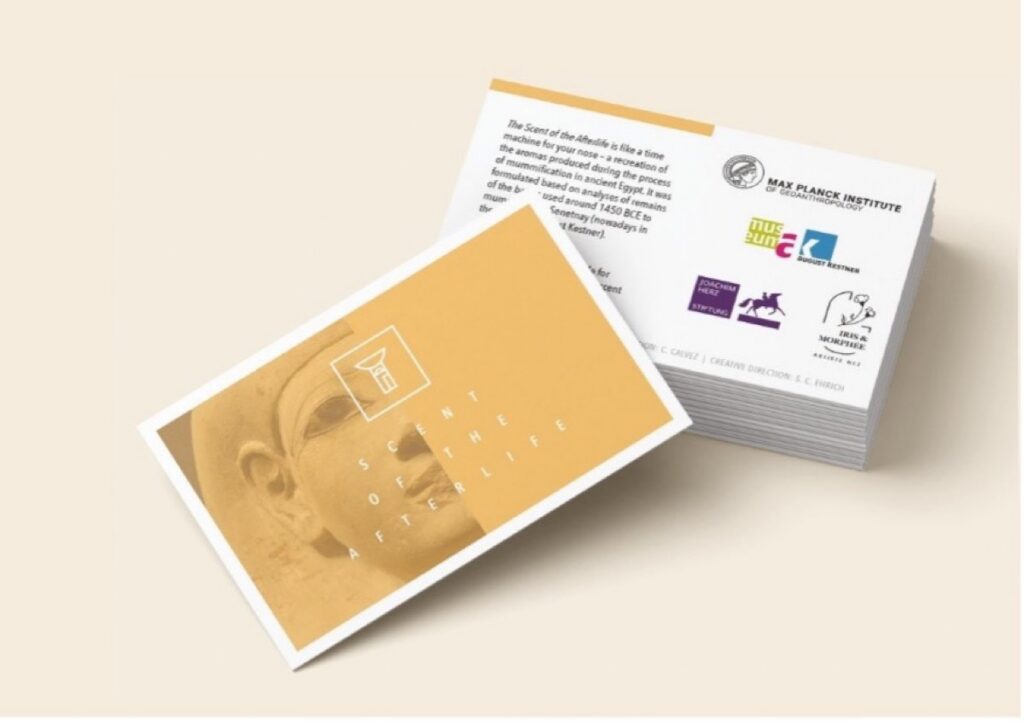

The portable scented card. The essence of the reproduced scent is inserted into the paper via scent printing. Michelle O’Reilly/CC BY

Museum display at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark. Barbara Huber/S.C. Ehrich et a;, 2026/CC BY

The portable scented card. The essence of the reproduced scent is inserted into the paper via scent printing. Michelle O’Reilly/CC BY

Her team’s analysis of the residue samples contained beeswax, plant oils, animal fats, bitumen, and resins from coniferous trees such as pines and larches, as well as vanilla-scented coumarin (found in cinnamon and pea plants) and benzoic acid (common in fragrant resins and gums derived from trees and shrubs). The resulting fragrance combined a “strong pine-like woody scent of the conifers,” per Huber, mixed in with “a sweeter undertone of the beeswax” and “the strong smoky scent of the bitumen.”

Huber’s latest paper, published in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, outlines an efficient workflow process for museums to add scents to their exhibits. First, she and her co-authors identified links between the scientific data and perfumery practice. Then they worked with perfumer Carole Calvez, who created a scent formulation befitting a museum environment.

“The real challenge lies in imagining the scent as a whole,” said Calvez, emphasizing that the task amounted to more than mere replication. “Biomolecular data provide essential clues, but the perfumer must translate chemical information into a complete and coherent olfactory experience that evokes the complexity of the original material, rather than just its individual components.”

The team also developed two formats to incorporate those scents in museums. One approach was a portable scented card, deployed at the Museum August Kestner in Hanover, Germany, as part of guided tours highlighting the relevant artifacts. The second was the construction of a fixed scent station at the Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus, Denmark. “The scent station transformed how visitors understood embalming,” Moesgaard Museum curator Steffen Terp Laursen said. “Smell added an emotional and sensory depth that text labels alone could never provide.”

Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, 2026. DOI: 10.3389/fearc.2025.1736875 (About DOIs)

W. Zhao et al, Journal of Archaeological Science, 2026. DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2026.106490

Visitors sniffing the "Scent of the Afterlife" card during a guided tour at the Museum August Kestner, Hannover, Germany Credit: Ulriki Dubiel/S.C. Ehrich et a;, 2026/CC BY

In 2023, scientists identified the compounds in the balms used to mummify the organs of an ancient Egyptian noblewoman, suggesting that the recipes were unusually complex and used ingredients not native to the region. The authors also partnered with a perfumer to re-create what co-author Barbara Huber (of the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and the University of Tübingen) dubbed “the scent of eternity.” Now Huber has collaborated with the curators of two museums to incorporate that eternal scent into exhibits on ancient Egypt to transform how visitors understand embalming.

As previously reported, Egyptian embalming is thought to have begun in the Predynastic Period or earlier, when people noticed that the arid desert heat tended to dry and preserve bodies buried in the desert. Eventually, the idea of preserving the body after death worked its way into Egyptian religious beliefs. When people began burying the dead in rock tombs, away from the desiccating sand, they used chemicals like natron salt and plant-based resins for embalming.

The procedure typically began by laying the corpse on a table and removing the internal organs—except for the heart. Per Greek historian Herodotus, “They first draw out part of the brain through the nostrils with an iron hook, and inject certain drugs into the rest” to liquefy the remaining brain matter. Next, they washed out the body cavity with spices and palm wine, sewed the body back up, and left aromatic plants and spices inside, including bags of natron. The body was then allowed to dehydrate over 40 days. The dried organs were sealed in canopic jars (or sometimes put back into the body cavity). Then the body was wrapped in several layers of linen cloth, with amulets placed within those layers to protect the deceased from evil. The fully wrapped mummy was coated in resin to keep moisture out and placed in a coffin (also sealed with resin).

Most of what we know about ancient Egyptian mummification techniques comes from a few ancient texts. In addition to a text called The Ritual of Embalming, Herodotus, in his Histories, mentions the use of natron to dehydrate the body. But there are very few details about the specific spices, oils, resins, and other ingredients used. Science can help fill in the gaps, particularly given the expanding array of methods for conducting biomolecular analysis, including various forms of gas chromatography.

For example, a 2018 study analyzed organic residues from the mummy’s wrappings with a technique called gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. They found that the wrappings were saturated with a mixture of plant oil, an aromatic plant extract, a gum or sugar, and heated conifer resin. A new paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science analyzed the chemical compositions of the odor-carrying volatile organic compounds (VOCs) associated with a broad sampling of balms and mummy tissues. The idea was to determine which odors were associated with organic embalming agents and which might have arisen from the process of decay.

Capturing the scent of the afterlife

Huber has previously worked on reconstructing residues on ancient incense burners excavated from Tayma, a walled oasis settlement in what is now Saudi Arabia that was part of a trade network—known as the Incense Route because it primarily transported frankincense and myrrh. Huber then turned her attention to Egyptian mummification. While most prior similar studies focused on samples gleaned from the bandages and tissues of actual mummies, she focused on the balms used to embalm accompanying organs stored in canopic jars.

Museum display at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark. Barbara Huber/S.C. Ehrich et a;, 2026/CC BY

The portable scented card. The essence of the reproduced scent is inserted into the paper via scent printing. Michelle O’Reilly/CC BY

Museum display at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark. Barbara Huber/S.C. Ehrich et a;, 2026/CC BY

The portable scented card. The essence of the reproduced scent is inserted into the paper via scent printing. Michelle O’Reilly/CC BY

Her team’s analysis of the residue samples contained beeswax, plant oils, animal fats, bitumen, and resins from coniferous trees such as pines and larches, as well as vanilla-scented coumarin (found in cinnamon and pea plants) and benzoic acid (common in fragrant resins and gums derived from trees and shrubs). The resulting fragrance combined a “strong pine-like woody scent of the conifers,” per Huber, mixed in with “a sweeter undertone of the beeswax” and “the strong smoky scent of the bitumen.”

Huber’s latest paper, published in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, outlines an efficient workflow process for museums to add scents to their exhibits. First, she and her co-authors identified links between the scientific data and perfumery practice. Then they worked with perfumer Carole Calvez, who created a scent formulation befitting a museum environment.

“The real challenge lies in imagining the scent as a whole,” said Calvez, emphasizing that the task amounted to more than mere replication. “Biomolecular data provide essential clues, but the perfumer must translate chemical information into a complete and coherent olfactory experience that evokes the complexity of the original material, rather than just its individual components.”

The team also developed two formats to incorporate those scents in museums. One approach was a portable scented card, deployed at the Museum August Kestner in Hanover, Germany, as part of guided tours highlighting the relevant artifacts. The second was the construction of a fixed scent station at the Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus, Denmark. “The scent station transformed how visitors understood embalming,” Moesgaard Museum curator Steffen Terp Laursen said. “Smell added an emotional and sensory depth that text labels alone could never provide.”

Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, 2026. DOI: 10.3389/fearc.2025.1736875 (About DOIs)

W. Zhao et al, Journal of Archaeological Science, 2026. DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2026.106490