- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 40 948

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

Unencrypted European communications are being targeted by Moscow.

Intelsat satellites are among those that have been targeted by Russia. Credit: Intelstat

European security officials believe two Russian space vehicles have intercepted the communications of at least a dozen key satellites over the continent.

Officials believe that the likely interceptions, which have not previously been reported, risk not only compromising sensitive information transmitted by the satellites but could also allow Moscow to manipulate their trajectories or even crash them.

Russian space vehicles have shadowed European satellites more intensively over the past three years, at a time of high tension between the Kremlin and the West following Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

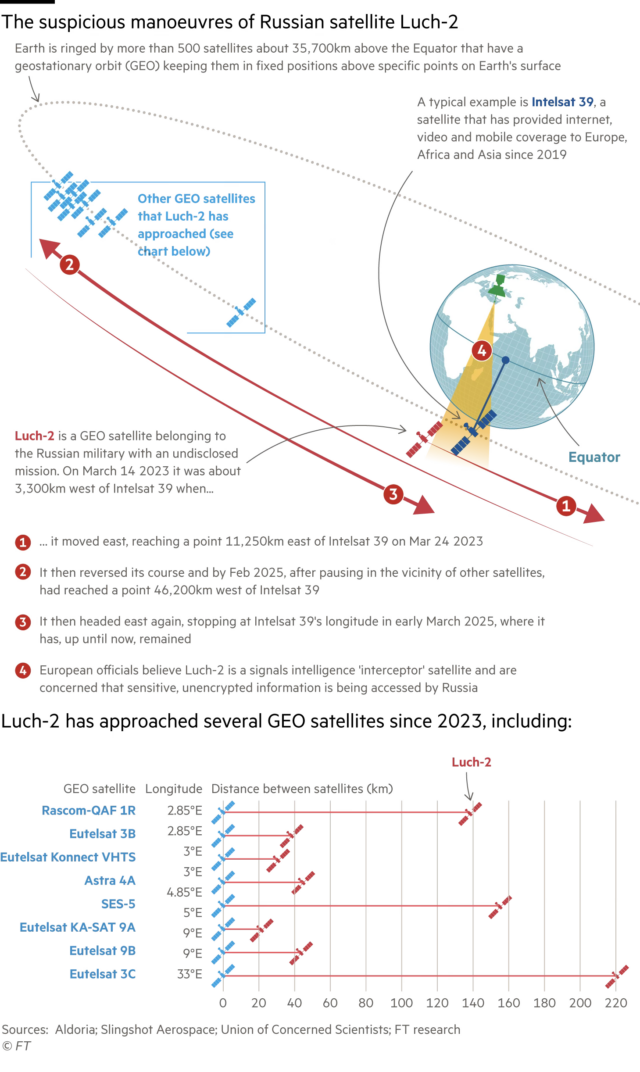

For several years, military and civilian space authorities in the West have been tracking the activities of Luch-1 and Luch-2—two Russian objects that have carried out repeated suspicious maneuvers in orbit.

Both vehicles have made risky close approaches to some of Europe’s most important geostationary satellites, which operate high above the Earth and service the continent, including the UK, as well as large parts of Africa and the Middle East.

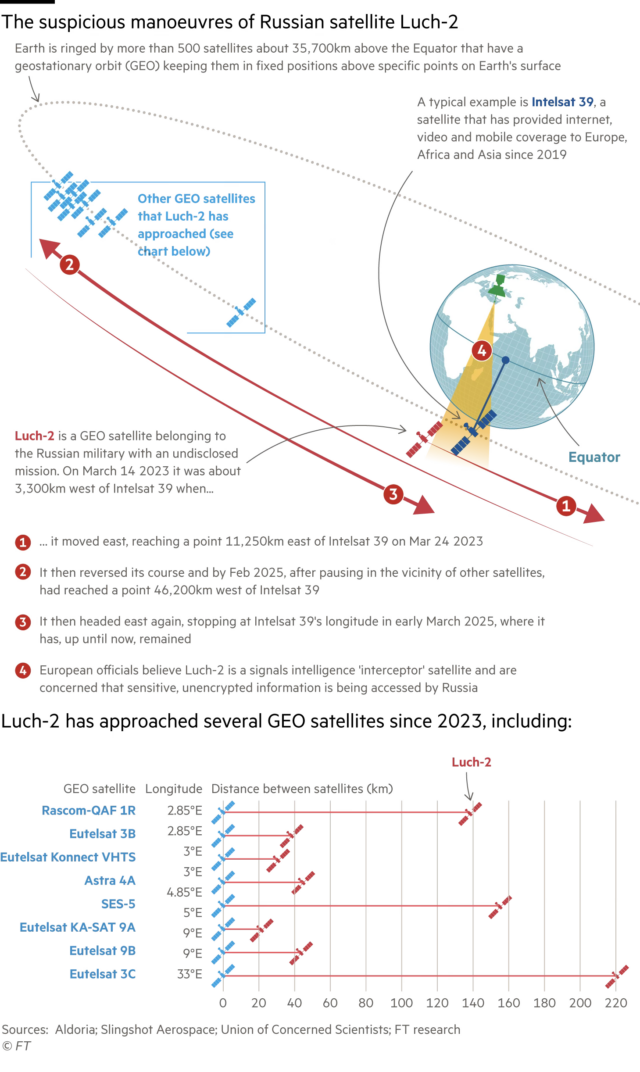

According to orbital data and ground-based telescopic observations, they have lingered nearby for weeks at a time, particularly over the past three years. Since its launch in 2023, Luch-2 has approached 17 European satellites.

Both satellites are suspected of “doing sigint [signals intelligence] business,” Major General Michael Traut, head of the German military’s space command, told the Financial Times, referring to the satellites’ practice of staying close to Western communications satellites.

A senior European intelligence official said the Luch vehicles were almost certainly intended to position themselves within the narrow cone of data beams transmitted from Earth-based stations to the satellites.

The official expressed concern that sensitive information—notably command data for European satellites—is unencrypted, because many were launched years ago without advanced onboard computers or encryption capabilities.

This leaves them vulnerable to future interference—or even destruction—once hostile actors have recorded their command data.

Credit: Financial Times

The maneuvers in space come as Russia steps up its “hybrid warfare” in Europe, including sabotage operations such as the severing of subsea Internet and power cables.

Intelligence and military officials are increasingly worried that the Kremlin could extend such disruptive activity into space, and is already developing the capability to do so.

While China and the US have developed similar technologies, Russia has one of the most advanced space-spying programs and has been more aggressive in its use of the vehicles to stalk satellites.

“Satellite networks are an Achilles heel of modern societies. Whoever attacks them can paralyze entire nations,” German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius said in a speech last September.

“The Russian activities are a fundamental threat to all of us, especially in space. A threat we must no longer ignore,” he added.

The European satellites approached by Luch 1 and 2 are primarily used for civilian purposes, such as satellite television, but also carry sensitive government and some military communications.

Luch 1 and Luch 2 are unlikely to have the capability to jam or destroy satellites themselves, the European intelligence official said. However, they have probably provided Russia with large amounts of data on how such systems could be disrupted, both from the ground and in orbit.

Maj. Gen. Traut said he presumed the Luch satellites had intercepted the “command link” of the satellites they approached—the channel linking satellites to ground controllers that allows orbital adjustments.

Analysts say that with such information, Russia could mimic ground operators, beaming false commands to satellites to manipulate their thrusters used for minor orbital adjustments.

Those thrusters could also be used to knock satellites out of alignment or even cause them to crash back to Earth or drift into space.

Intelligence gathered by Luch 1 and 2 could also help Russia coordinate less overt attacks on Western interests. Monitoring other satellites can reveal who is using them and where—information that could later be exploited for targeted ground-based jamming or hacking operations.

The Luch vehicles were “maneuvring about and parking themselves close to geostationary satellites, often for many months at a time,” said Belinda Marchand, chief science officer at Slingshot Aerospace, a US-based company that tracks objects in space using ground-based sensors and artificial intelligence.

She added that Luch 2 was currently “in proximity” to Intelsat 39, a large geostationary satellite that services Europe and Africa.

Since its launch in 2023, Luch-2 has hovered near at least 17 other geostationary satellites above Europe serving both commercial and government purposes, Slingshot data shows.

“They have visited the same families, the same operators—so you can deduce that they have a specific purpose or interest,” said Norbert Pouzin, senior orbital analyst at Aldoria, a French satellite tracking company that has also shadowed the Luch satellites. “These are all Nato-based operators.”

“Even if they cannot decrypt messages, they can still extract a lot of information… they can map how a satellite is being used, work out the location of ground terminals, for example,” he added.

Pouzin also said that Russia now seemed to be ramping up its reconnaissance activity in space, launching two new satellites last year named Cosmos 2589 and Cosmos 2590. The vehicles appear to have similarly maneuvrable capabilities to Luch-1 and Luch-2.

Cosmos 2589 is now on its way to the same range as geostationary satellites, which orbit 35,000 km above Earth, Pouzin said.

But Luch-1 may no longer be functional. On January 30, Earth telescopes observed what appeared to be a plume of gas coming from the satellite. Shortly after, it appeared to at least partially fragment.

“It looks like it began with something to do with the propulsion,” said Marchand, adding that afterwards there “was certainly a fragmentation,” and the satellite was “still tumbling.”

© 2026 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.

Intelsat satellites are among those that have been targeted by Russia. Credit: Intelstat

European security officials believe two Russian space vehicles have intercepted the communications of at least a dozen key satellites over the continent.

Officials believe that the likely interceptions, which have not previously been reported, risk not only compromising sensitive information transmitted by the satellites but could also allow Moscow to manipulate their trajectories or even crash them.

Russian space vehicles have shadowed European satellites more intensively over the past three years, at a time of high tension between the Kremlin and the West following Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

For several years, military and civilian space authorities in the West have been tracking the activities of Luch-1 and Luch-2—two Russian objects that have carried out repeated suspicious maneuvers in orbit.

Both vehicles have made risky close approaches to some of Europe’s most important geostationary satellites, which operate high above the Earth and service the continent, including the UK, as well as large parts of Africa and the Middle East.

According to orbital data and ground-based telescopic observations, they have lingered nearby for weeks at a time, particularly over the past three years. Since its launch in 2023, Luch-2 has approached 17 European satellites.

Both satellites are suspected of “doing sigint [signals intelligence] business,” Major General Michael Traut, head of the German military’s space command, told the Financial Times, referring to the satellites’ practice of staying close to Western communications satellites.

A senior European intelligence official said the Luch vehicles were almost certainly intended to position themselves within the narrow cone of data beams transmitted from Earth-based stations to the satellites.

The official expressed concern that sensitive information—notably command data for European satellites—is unencrypted, because many were launched years ago without advanced onboard computers or encryption capabilities.

This leaves them vulnerable to future interference—or even destruction—once hostile actors have recorded their command data.

Credit: Financial Times

The maneuvers in space come as Russia steps up its “hybrid warfare” in Europe, including sabotage operations such as the severing of subsea Internet and power cables.

Intelligence and military officials are increasingly worried that the Kremlin could extend such disruptive activity into space, and is already developing the capability to do so.

While China and the US have developed similar technologies, Russia has one of the most advanced space-spying programs and has been more aggressive in its use of the vehicles to stalk satellites.

“Satellite networks are an Achilles heel of modern societies. Whoever attacks them can paralyze entire nations,” German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius said in a speech last September.

“The Russian activities are a fundamental threat to all of us, especially in space. A threat we must no longer ignore,” he added.

The European satellites approached by Luch 1 and 2 are primarily used for civilian purposes, such as satellite television, but also carry sensitive government and some military communications.

Luch 1 and Luch 2 are unlikely to have the capability to jam or destroy satellites themselves, the European intelligence official said. However, they have probably provided Russia with large amounts of data on how such systems could be disrupted, both from the ground and in orbit.

Maj. Gen. Traut said he presumed the Luch satellites had intercepted the “command link” of the satellites they approached—the channel linking satellites to ground controllers that allows orbital adjustments.

Analysts say that with such information, Russia could mimic ground operators, beaming false commands to satellites to manipulate their thrusters used for minor orbital adjustments.

Those thrusters could also be used to knock satellites out of alignment or even cause them to crash back to Earth or drift into space.

Intelligence gathered by Luch 1 and 2 could also help Russia coordinate less overt attacks on Western interests. Monitoring other satellites can reveal who is using them and where—information that could later be exploited for targeted ground-based jamming or hacking operations.

The Luch vehicles were “maneuvring about and parking themselves close to geostationary satellites, often for many months at a time,” said Belinda Marchand, chief science officer at Slingshot Aerospace, a US-based company that tracks objects in space using ground-based sensors and artificial intelligence.

She added that Luch 2 was currently “in proximity” to Intelsat 39, a large geostationary satellite that services Europe and Africa.

Since its launch in 2023, Luch-2 has hovered near at least 17 other geostationary satellites above Europe serving both commercial and government purposes, Slingshot data shows.

“They have visited the same families, the same operators—so you can deduce that they have a specific purpose or interest,” said Norbert Pouzin, senior orbital analyst at Aldoria, a French satellite tracking company that has also shadowed the Luch satellites. “These are all Nato-based operators.”

“Even if they cannot decrypt messages, they can still extract a lot of information… they can map how a satellite is being used, work out the location of ground terminals, for example,” he added.

Pouzin also said that Russia now seemed to be ramping up its reconnaissance activity in space, launching two new satellites last year named Cosmos 2589 and Cosmos 2590. The vehicles appear to have similarly maneuvrable capabilities to Luch-1 and Luch-2.

Cosmos 2589 is now on its way to the same range as geostationary satellites, which orbit 35,000 km above Earth, Pouzin said.

But Luch-1 may no longer be functional. On January 30, Earth telescopes observed what appeared to be a plume of gas coming from the satellite. Shortly after, it appeared to at least partially fragment.

“It looks like it began with something to do with the propulsion,” said Marchand, adding that afterwards there “was certainly a fragmentation,” and the satellite was “still tumbling.”

© 2026 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.